β-catenin: An inquiry into the development of endometrial cancer

By Vina Senthil

In the United States, endometrial carcinoma is the most common type of gynecological cancer, with more than 66,000 new cases reported in 2023.⁸ A type of uterine cancer, endometrial cancer (EC) is the abnormal growth of mutated cells, cancer cells, in the endometrium, the inner lining of the uterus. Risk factors for EC include older age, early menstruation, or late menopause, obesity, and changes in the balance of estrogen and progesterone in the body.³ (Fig. 1) ¹²³⁴⁵⁶⁷⁸⁹⁰

Endometrial cancer is cancer of the endometrium - the thick inner lining of the uterus.

Source: Endometrial cancer video & image. (n.d.). Retrieved March 18, 2024, fromhttps://www.columbiadoctors.org/health-library/multimedia/endometrial-cancer/

Despite its prevalence and the significant progress made in oncological research over the years, the incidence and mortality rates of EC have increased, with the number of new annual cases in 2023 nearly double the amount reported in 1987, about 35,000 cases.² EC disproportionately affects Black women in the United States. Black women are also more likely to develop the more aggressive subtypes of EC, such as carcinosarcoma, serous, clear-cell, mixed-cell, and high-grade endometrial carcinomas.⁹ They are also nearly twice as likely to die from the disease in comparison to white women. This is due to inequalities between white and Black women that persist throughout the treatment process. Black women experience more delays in proper screening and diagnosis, often resulting in late-stage detection of the disease. Furthermore, Black women have not been adequately represented in clinical trials for drugs that could potentially treat EC, so a difference in clinical outcomes is less likely to be attributed to treatments received.¹⁰

Dr. Andrew Gladden, an associate professor in the Department of Pathology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine, asserts that EC is incredibly underfunded and understudied. Among many other motivations, this fact is a driver of his research team’s interest in the disease. The Gladden Lab investigates the various molecular subtypes of EC.

Dr. Andrew Gladden

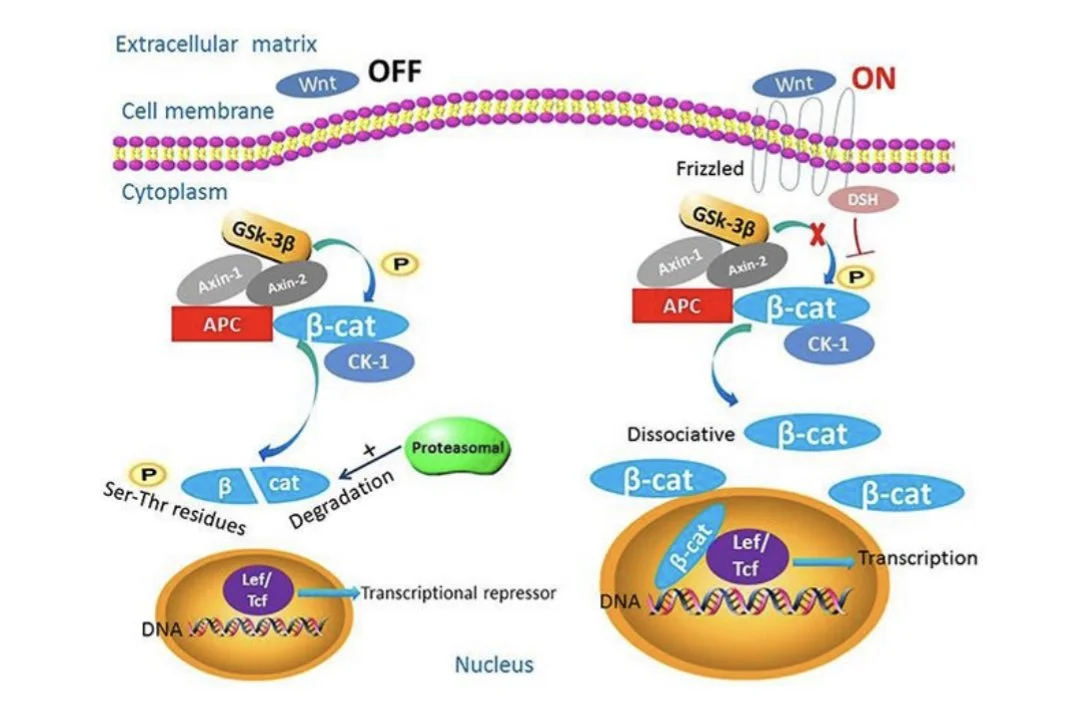

One of the lab’s ongoing projects focuses on the beta-catenin (β-catenin) protein’s role in the development of EC. β-catenin is encoded by the CTNNB1 gene. It functions in the adherens junction, a space linking cells together and connecting to the structural actin protein filament, to facilitate the adhesion of cells. β-catenin also acts in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, where it contributes to embryonic development and homeostasis of adult tissues.⁶ A signaling pathway, like the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, is a series of chemical reactions controlled by specific proteins. As shown by studies in colon and endometrial cancer, numerous genes in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway are mutated in cancer. In EC cases, deletion of exon 3 of the CTNNB1 gene in mouse models is linked to endometrial hyperplasia, a condition in which the lining of the uterus becomes irregularly thick, signifying cancer.⁴ An exon is a region of DNA that is transcribed, eventually contributing to the production of a protein. Transcription is the process by which DNA is “read” and converted to mRNA, where it may eventually be translated to proteins. Amino acids encoded in exon 3 of theCTNNB1gene get modified by other proteins in turn, activating the degradation of β-catenin. This is a critical function, as when there is more β-catenin activity, the initiation of cancer is more likely to occur.⁴

In endometrial cancer, mutations to β-catenin can result in changes to the protein’s localization, or its “final destination” in the cell. Typically, β-catenin is expressed in the membrane, or outer layer, of a cell. β-catenin expression in the cytoplasm is low due to the activity of destruction complexes, which consist of specific proteins that work together to regulate cytoplasmic β-catenin. When the destruction complex becomes inactive, β-catenin accumulates in the cytoplasm and travels to the nucleus of the cell, where it serves as a transcription factor.⁴ A transcription factor is a protein that controls the rate of transcription of DNA. As a transcription factor, β-catenin allows for the programming of genes downstream in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. These genes include cyclin D1 and CD44, and play an eventual role in epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis.⁴ Epithelial-mesenchymal transition is the process by which epithelial cells, cells that line the surfaces of the body (skin, cavities, inner lining of uterus), lose some of their adhesive properties, while gaining the ability to migrate, turning into mesenchymal stem cells.¹² Mesenchymal stem cells are cells that can convert to different types of cells and may stimulate the development of tumors.⁵ (Fig. 2)

When Wnt, a ligand or molecule that binds to a cell membrane receptor, is not present, β-catenin is degraded. When Wnt is present, the destruction complex is inactive and β-catenin localizes to the nucleus.

Source: Gao C., Wang Y., Broaddus R., Sun L., Xue F., Zhang W. Exon 3 mutations ofCTNNB1drivetumorigenesis: a review. Oncotarget. 2018; 9: 5492-5508. Retrievedfromhttps://www.oncotarget.com/article/23695/text/

After analyzing multiple human tumors with mutations in β-catenin, Dr. Gladden’s research team discovered that while it was expected for β-catenin to localize to the nucleus, in some tumors–it was found in the cytoplasm. The team’s next question was whether the genetic makeup of β-catenin corresponded to the variability in localization.¹

To explore this question, the team used spatial transcriptomics, a “molecular profiling method” that enables researchers to obtain information regarding what and where gene activity occurs in a tissue sample.¹² They began by carrying out whole-transcriptome analyses of primary human tumors with β-catenin mutations, hypothesizing that cases where β-catenin localization was to the nucleus would feature a different β-catenin transcriptional readout, or genetic makeup, than in cases where β-catenin localization was to the cytoplasm. They found that in cases of nuclear and non-nuclear localization, β-catenin had some genetic differences. For example, β-catenin that was localized to the nucleus has higher expression of the gene TACSTD2, which encodes the protein Trop2. Trop2 is currently being targeted by a drug designed to treat EC.⁷ The research team’s hypothesis was correct–β-catenin’s transcriptional readout and its localization were indeed linked.

Dr. Gladden says these findings open doors to better treatments and thus better clinical outcomes for patients battling endometrial cancer. The team’s findings can be applied to the creation of biomarkers to help stratify types of endometrial cancer based on the localization of β-catenin. This may enable clinicians to provide more personalized treatments to patients with endometrial cancer, potentially increasing their chances of survival and successful recovery.¹

References

Interview with Andrew Gladden, Ph.D. 02/26/2024

Endometrial cancer rates rising alarmingly, particularly among Black women. (2023, December 19). News-Medical.https://www.news-medical.net/news/20231219/Endometrial-cancer-rates-rising-alarmingly-particularly-among-Black-women.aspx

Endometrial cancer—Symptoms and causes. (n.d.). Mayo Clinic. Retrieved March 4, 2024, fromhttps://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/endometrial-cancer/symptoms-causes/syc-20352461

Gao C., Wang Y., Broaddus R., Sun L., Xue F., Zhang W. Exon 3 mutations ofCTNNB1drivetumorigenesis: a review. Oncotarget. 2018; 9: 5492-5508. Retrieved from https://www.oncotarget.com/article/23695/text/

Liu, J., Xiao, Q., Xiao, J., Niu, C., Li, Y., Zhang, X., Zhou, Z., Shu, G., & Yin, G. (2022). Wnt/β-catenin signalling: Function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities.SignalTransduction and Targeted Therapy,7(1), 1–23.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-021-00762-6

Molly L. Parrish, Andrew B. Gladden, Russell R. Broaddus. Location, location, location: Why cellular localization of mutant β-catenin matters in endometrial cancer [abstract]. In: Proceedings of the AACR Special Conference on Endometrial Cancer: Transforming Care through Science;2023 Nov 16-18; Boston, Massachusetts. Philadelphia (PA): AACR; Clin Cancer Res2024;30(5_Suppl):Abstract nr PR008.

Parrish, M. L., Broaddus, R. R., & Gladden, A. B. (2022). Mechanisms of mutant β-catenin in endometrial cancer progression.Frontiers in Oncology,12.https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2022.1009345

Pinheiro, P. S., Medina, H. N., Koru-Sengul, T., Qiao, B., Schymura, M., Kobetz, E. N., &Schlumbrecht, M. P. (2021). Endometrial cancer type 2 incidence and survival disparities within subsets of the us black population. Frontiers in Oncology, 11, 699577.https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.699577

Racial disparities in endometrial cancer: Improving diagnosis and treatment. (2023, June 22).Fred Hutch.https://www.fredhutch.org/en/news/blog/2023/06/racial-disparities-endometrial-cancer-improving-diagnosis-treatment.html

Racial disparities in endometrial cancer mortality. (2022, May 23). Penn LDI.https://ldi.upenn.edu/our-work/research-updates/racial-disparities-in-endometrial-cancer-mortalit

Santos Ramos, F., Wons, L., João Cavalli, I., & M.S.F. Ribeiro, E. (2017). Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer: An overview.Integrative Cancer Science and Therapeutics,4(3). https://doi.org/10.15761/ICST.1000243

Spatial transcriptomics. (n.d.). 10x Genomics. Retrieved March 18, 2024, fromhttps://www.10xgenomics.com/spatial-transcriptomics